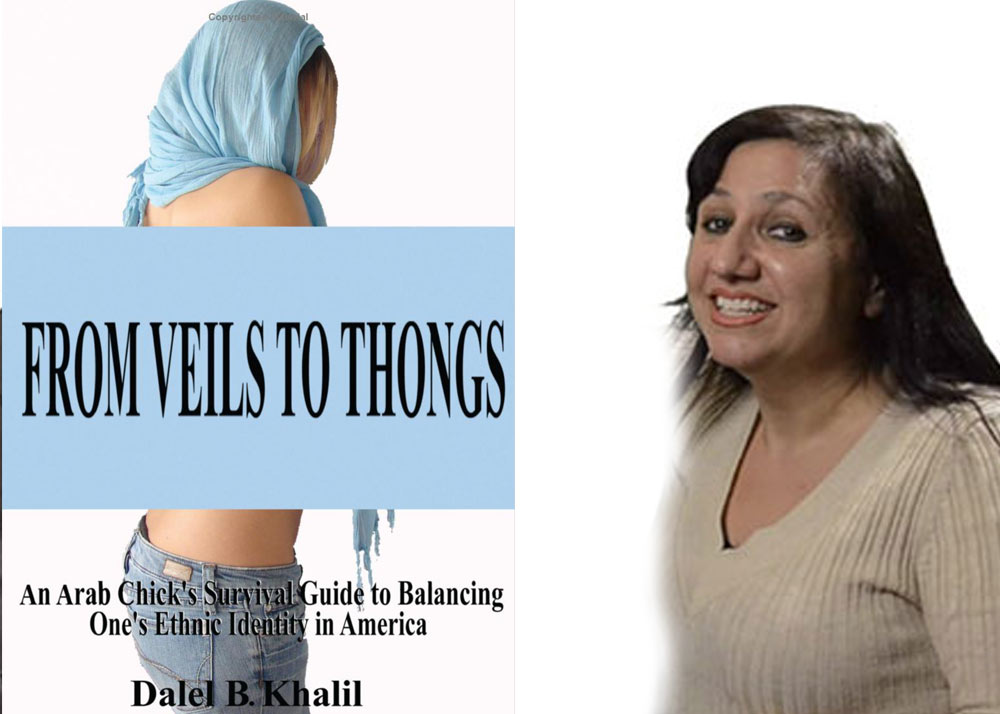

From Veils to Thongs

An Interview with Author Dalel Khalil

ArabLounge Magazine > Lifestyle| February 2010

ArabLounge Magazine > Lifestyle| February 2010

We were lucky enough to interview Dalel Khalil, the author of From Veils to Thongs: An Arab Chick's Survival Guide to Balancing One's Ethnic Identity in America; her recent book that has everyone laughing and nodding their heads about the challenges and humor of culturally navigating between East and West. The subtitle of the book says it all. Here's what she has to say about a whole range of interesting topics. If you haven't had the chance to read the book, we suggest you read it, read it now. You will not regret it!

What inspired the book?

DK: To be honest, I didn't write this book. It wrote me. The honest truth is that I just had to get all these funny things out of my head, because as a creative person—as an artist—I just couldn't keep it inside. It had to come out. I had no control over it—the cultural clashes are just too funny. The most I thought is that I could write this little mini-book, like the ones they sell at bookstores near the check-out lines. So, I pounded out 4 pages and told everyone, "Hey, I have a book!" Then I went to Syria, and came back with more material than I could handle. Everything just started spewing out and my fingers couldn't type fast enough to keep up with the funny thoughts that went through my head. That's when I realized I really had a book.

I know it would be better PR if I said "After 9/11 I felt compelled to fight negative Arab stereotypes" but as altruistic as that might sound, that's not the case. However, during the course of writing I discovered that this book could really help some Arabic girl who is struggling with her bi-cultural identity, regardless of where she lives—in Paris, Sydney, or Kansas City. And, I thought, if I can help just one person feel less alone, less isolated—if some girl is alone in her room crying her eyes out and she picks up this book and laughs, and it helps her get through her pain—then I'm happy. Then I will have succeeded. And the more I wrote, the more I began to realize how this could help Americans understand us better as well, because, unfortunately, they only get distorted information from the media. And they really don't know what the average Arab "chick" is all about. All they seem to know about us is that we're "oppressed". I mean, look in bookstores, the market is oversaturated with dark, dreary, depressing stories about the "oppressed" Arab woman. Bookshelves are lined with titles like, "Veil this... Veil that... Beyond the Veil... Inside the Veil... " And I want to say, "Enough already! Okay! We're oppressed! Now can we please have some fun, jeez!" Although those stories need to be told, the reality is that most Arabic girls aren't princesses running away from royal guards or narrowly escaping death—they are just ordinary average Arab chicks; they are real people—they are your neighbors, co-workers and classmates. My book examines the challenges of the average Arab chick who lives "Outside the Kingdom"... waaaaay Outside the Kingdom... like in Brooklyn, USA.

Would you say that you have now successfully mastered the balance between two cultures?

DK: Yes, most definitely, but I say that with the utmost humility. It took a very long time for me to get here, but I think I've gotten to the point where I am very firm in both=2 0my American side and my Arabic side, although my Arabic side needs a little more work. I can pick and choose the good things about each culture, cherish and enjoy them, and throw away the bad. And I can bounce from one culture to the next without skipping a beat. I still can't cook though. And I can't successfully crack bizzer the right way... and sometimes I burn Turkish coffee... so, I do still have some tough challenges ahead of me.

What were your biggest challenges growing up, with respect to balancing two "diametrically opposed" cultures?

DK: Everything was a challenge for me. But I think the biggest overall challenge was keeping grounded in who I was—being authentic and being true to myself—no matter what cultural messages were pressuring me. It was critical for me not to allow either cultural expectation to control me, but rather for me to define who I am—on my own terms. I am very stubborn in that way. In fact, that concept is so important to me that the very first page of my book is a quote from Shakespeare, "To thine own self be true." My situation is particularly complicated because my parents were cousins, and my mother's side was raised very liberally, while my father's side was very traditional. And my particular family was right smack in the middle. It's important to note that my parents were generally very cool with things. My mother encouraged us to live life to the fullest, but the cultural messages and living day-to-day within the cultural mindset, had such a strong influence on me. So, for example, at 15 years old, I have my Sito constantly saying, "Go to Syria and find a husband!" but at the same time, at 15 years old, I flew plane. I actually took my first pilot lesson, with my dad sitting in the backseat of the plane. So, the cultural messages and expectations, especially as a female, couldn't have been farther apart for me. Just after college everybody around me was getting married, and I couldn't understand why. I couldn't understand getting married that early when there were so many adventurous things to do in life. To me the exciting part was just starting. I want to emphasize there is absolutely nothing wrong with that. To each, her own. But for me, I had ambitions to live in NY, be an actress, travel the world and just live life before settling down. And I couldn't figure it out, I thought "What's going on? Is it me? Am20I being overly ambitious? Should I just go get married?" But there was no way I could NOT live my dreams, first. So, my basic life's direction was strongly impacted. And of course, men. Do I marry an Arab guy or an American guy? Thankfully now, Arab-Americans are more involved with their cultures, but back in the day, there were very few who were equally connected to both. It was more the case that they were either more Americanized, or a FOB (Fresh off the boat) Arab. And, again, I'm in the middle, so I need someone who can relate to both my worlds. All my life, I swore I would never marry an Arab man; I wanted an American so we could do all kinds of adventurous things, like go scuba diving together. I wanted to be with someone who would have an open mind, and allow me to be free—to be my own person—without all the demanding cultural expectations and pressure. But I swear, the moment I went to a hafli, all that flew out the window, because it didn't feel right with an American guy. I needed to dupkee with my husband, and he needs to hang with the sheb and smoke cigarettes and drink arak. He needs to call old guys he's never met before, "Uma or Jidu". He's gotta look into my eyes and sing "Intay Omri" with the sexy passion that only an Arab man would know. Defining one's self on one's own terms is critical, and with such strong conflicting messages from either side, it's easy to be tricked. For example, an Arabic girl is expected to behave in a certain way, but if the expectations are too much pressure for her, she may either conform,=2 0rebel, or just plain crack up. If she is obedient without it being her choice, she will be resentful. If she rebels, and wakes up one day realizing she's living a lie, she also will feel pain in her heart—because rebellion is just another form of control. Each person must define her own identity and live authentically in that way as best she can. So, again, I think that remaining true to myself was the greatest challenge I have faced, without even being aware that I was facing it.

If you had a daughter, how would you make it easier for her to balance the struggle between two cultures.

DK: I'd make her read my book ;) Then if she still didn't understand, I would send her to the finest psychological counseling available in the world. Or I would keep her locked up in her room until she was 40 years old. Make that 41! Seriously, though, I would first make her love both her Arabic culture and American cultures, just as my mother did. And I would explain to her that there are good and bad things in both cultures, and encourage her to embrace the good, bad and ugly in both—but then, really enjoy the good. I would encourage her to live life to the fullest and stress that there is nothing wrong with being conservative, even though all the American cultural messages suggest otherwise. But above all, I would encourage her to follow her own heart and be true to herself. She must know herself, and no matter what happens in her life, not forget who she is and where she comes from. I would support her to be strong, solid, grounded, and firm in her beliefs so that she can withstand any pressure that might take her down a20negative path.

Your book's title From Veils to Thongs is very provocative. How do you feel it will be received in an Arab community that still appears very conservative?

DK: I was concerned about the title and cover, so I asked members of the Arab community—including Muslims—their opinions. And they were very open because they understood where my heart was, and what I was trying to say. When they understood the meaning behind it, it made perfect sense to them, and they couldn't wait to read it. So, I am very confident that once people read this book, they will love it. For those who haven't read it yet, it promotes Arabic culture in such a positive light that it might very well be mistaken for propaganda. In fact, I should be paid by Arabic governments for increasing tourism! I worked very hard to clarify things because it's critical to understand what this title means. In fact, I include an 18 page disclaimer because it is so important for all readers (Arab and American) to understand where I am coming from. I clearly state... "This book has absolutely nothing to do with religion whatsoever, so don't try to make something out of nothing... .This book has nothing to do with veils and thongs, as in the religious attire or lingerie, but rather symbolically represents the mentality behind the basis of each. It is a metaphor of the extremes. It speaks to those who left a conservative society (the East) to emigrate to a liberal one (the West). Veils representing all things traditional; thongs representing all things liberal. My worlds are two—saturated and represented by both. And both cultures are equally my birthright. No woman has ever had to have physically worn either to understand life in this realm." And ALL Arab women—I don't care if you are an Arab Christian, an Arab Muslim, or an Arab Atheist... An Arab chick, is an Arab chick, is an Arab chick... And if you're an Arab chick—you live under a "mental" veil. If you're an Arab Chick, you've been bombarded with "ibe" (even when you weren't doing anything wrong). As a matter of fact, I think one of the first words Arabic females learn, is the word "ibe". I'm not saying to get rid of it altogether—not at all—trust me, ibe is a good thing, it keeps us in line. We just have to be careful not to overdo it. All I'm saying is that if you're an Arab chick, you have a clear understand the meaning of shame, honor, family, faith, etc. And the truth of the matter is, that it really isn't an "Arab" thing at all, it extends to all traditional chicks regardless of religion or race—Indian, Asian, Jewish—even the Amish. It's all about coming from a traditional world (veils) while simultaneously trying to live and integrate in a Western one (thongs). Not only is the title provocative, but the cover is, too. I want to make it clear that the cover is a representation of me—Dalel B. Khalil—and does not represent any other Arab chick, but me. It is who I am—not anyone else in the world. So, it's as if I am holding up a photograph of myself and showing you my picture. You cannot take my photo, turn it around to yourself and say "Hey! You're offending me!" You cannot. You cannot because it is not you—it is me. And nobody—and I mean nobody—c an take the pain and suffering I endured as an Arab chick away from me. No one can deny me my pain—the pain of double standards and hypocrisy—and claim it only for themselves. The girl on the cover is most certainly not wearing a hijab, she is wearing a veil. And although the girl is actually a model, she represents me. So, the people who actually read this book will absolutely love it and the people who refuse to read it, will reject it no matter what's inside. And there's nothing more I can do about it. I've explained myself to the best of my ability. Besides... if it's so taboo or horrible, why do they openly sell veils right next to racy thongs in the souks all over the Middle East? Furthermore, why do the thongs in the Middle East make Victoria's Secret's thongs look like K-Mart bloomers? So, I would say if you're offended by it, don't read it. Honestly. Read something else. I won't be offended.

Not only is your book informative to a non-Arab individual but it is also hilarious. How do you think humor helps the messages of the book resonate with readers?

DK: Thank you so much, I appreciate that. Humor is an amazing tool. I think it's a gift from God to help us deal with the unbearable things in life, and keeps us from completely cracking up. Humor humbles us. It breaks us down to our very core and presents the truth in way that is undeniable and digestible. Essentially, it protects us from the shock of truth, while simultaneously, allowing us to receive it, and possibly even serve as a catalyst for change. So, things that are normally uncomfortable to talk about can be said in a way that allows the reader to hear and absorb ideas that she would not be able to, if they were stated more directly. The reason Steven Colbert is so funny is because he takes a simple idea and takes it so over the top, that it is impossible not to see the absurdity in it. He makes you see how utterly ridiculous something is, just by exaggerating it to the extreme. I think the humor in this book really forces the reader to look at herself, her life and her situation. She might laugh at it, condemn it or deny it—but either way, in the back of her mind, she will question it. Something in this book is going to touch a nerve, and other things are just going to make the reader appreciate her life even more. The back cover of my book states: Arabic women deal with very serious issues they often feel powerless to change. This is true, whether we want to admit that or not. But since we don't talk about certain things, the issues just keep getting swept under the rug, and it keeps getting bigger. I wrote the Sperm in the Air Theory chapter as a result of dealing with my anger over many issues when I was a teenager. There was simply no other sane way to deal with it. And I think humor is the only thing that is going to allow us to explore even greater, more sensitive issues that lie ahead. It must be done delicately though, with courage and without judgment. And I think once we embrace our own imperfections, the cultural bridge will strengthen. American readers, no doubt, will look at Arabs in a brand new way, because up until now, the only images out there are of suffering, oppressed or dangerous people—all without a sense of humor. The average American's only exposure of us is on television, where we're angry and shouting like mad men about something political. That's it. So, unfortunately, they don't get a chance to see the positive side. But when they read this, they will not only learn that we are warm, loving and affectionate, but also that we're some pretty funny people. So, essentially, the humor allows both Western and Eastern people to realize that we are really all the same underneath.

Of all the humorous quirks that Americans have in the eyes of Arabs and vice versa, which particular quirks have been the most impactful and/or irritating to you?

DK: Being held hostage! I cannot stand being held hostage! I am a very individualistic person. I love freedom, privacy, and movement, so I need my space. As Arabs we love each other, sometimes, too much. We're very affectionate and we do that hospitality thing. The problem is that we don't know how to let go, even if it's just for a little while. We always need be around each other—but me, I need to breathe. So, when I'm at somebody's house and they kidnap me and hold me hostage with their hospitality, and I tell them, "I love you, but I have to go now" they feel insulted. They ask, "Why? You just got here?" (I say) "Yeah... I just got here 5 freekin' hours ago!" ... (they say) "You can't go! Here, drink matè!." ... (I say) "I love you, but I have to go, now!" ... (they say) "No! No! No! You can't! You have to watch the videos of my cousin's wedding!" Three more hours have passed and they've barricaded the room – you're just not getting out. You ain't leavin'. That kills me. There are many more irritating things, like the intrusiveness, you know, of people not minding their own business, but rather being astutely aware of yours. And the control issues... And the excessive drama. Oh, we LOVE drama. We can make an Emmy award-winning soap opera out of the teeniest tiniest incidents, just to entertain ourselves.

You discussed your mother's "very open, vocal and non-secretive plan...to divorce her Syrian-farmer husband as soon as he got his green card." Ironically they stayed married for 47 years with your father by her side until the end. When did her intentions change?

DK: Underneath his typical macho Arab man façade, he genuinely has a good heart. He is a kind, sweet, generous, honorable, humble, and loving good man. And after a while, she began to open her eyes and see him differently. She began to love him, flaws and all. Incidentally, after she passed, my father commissioned a massive icon of Christ the Pantocrator in our church, to honor my mother.

How has the advent of niche internet dating and specifically ArabLounge impacted the dating world for Arab Americans?

DK: Are you kidding? I wish we had this growing up! When we wanted to contact a guy, we used to have to wait till nobody was around, sneak to the payphone down the street, stake a girl on the lookout a block away, and call boys from the payphone so we could secretly meet them at the mall. And not only try to look "cool" doing it, but not get caught by an intrusive relative in the process! Technological advances have changed everything. Now people have the internet, cell phones, email, IM, etc. it's so much easier—there is really no suffering involved. Come to think of it, I think it's too easy—no fun, no adventure. I mean, where's the thrill in that? This generation is too spoiled! I think ArabLounge should shut down operations immediately. Let those lazy bums work for it! And besides, I think it's wrong! Do you know how many sitos you're putting out of business? Do you know how many intrusive khaltos you're laying off with your technological match-making garbage thingy?! What are the ladies going to gossip about if they don't see you openly flirting with a guy right in front of their eyes? Seriously though, I think it's the breakthrough everyone needed. Life is completely different now and people want more out of life without having to compromise their values, traditions or culture. They want to explore and see who is their best option, rather than settling for what's in their backyard. ArabLounge has brought worldwide opportunities to people whose only chance of meeting someone used to be at their khalto's house, or at a hafli—and come on, everyone's got their eyes on y ou, either way. And believe me, your khalto doesn't always understand what "hot" is. And trust me, neither does your sito. So, if you're an independent, working Arab chick, where are you going to meet someone who you can truly relate to, without the whole world knowing about it? Viola! ArabLounge, baby!

Which Arab-Americans have been an influence on your life one way or the other?

DK: That's a hard one because we really didn't have role models growing up. If I were 15 years old now, I'd have to say it would be Shakira, because she just went out and did her thing. She's bold and gutsy. Other than that, I would have to credit my mother because she really instilled in us a deep love for our culture, as well as others. She loved life and was passionate about it. We were raised in America as if we were raised in Syria—always having a "sahara" at our restaurant. She loved when we danced, played the drums, sang and just were together. She loved family. I have an enormous amount of respect and admiration for my father as well. He came to this country and didn't speak a word of English. He had a third grade education, and yet lived the American dream. He worked hard and earned his own success. He loves this country and genuinely appreciates all that it has done for him. He puts God first and constantly gives to the needy, hungry, hopeless and forgotten. He is an honorable man. Both taught me values and traditions. And they didn't let their children get "lost" in this new country. They gave us freedom to explore, but combined it with traditional values—thereby giving us the ability 'balance" both worlds. So, I truly admire them both.

What are your plans for the future? Will you be writing more books on this topic?

DK: Oh, most definitely! The movie is next. Then, a sitcom. Then another book. There are just so many ideas I have and things I want to do. My mind races every day with new ideas.

What did you do before become a writer? How did that experience shape you?

DK: I worked in radio broadcasting for 8 years, as a morning show co-host, anchor, reporter and talk show host for 3 of Pittsburgh's top radio stations. Working as a morning show co-host with the Aswaad station was the most fun because I got to use my talent the most by doing character voices and prank calls. The most important thing, however, was that it helped me feel less isolated. When I was there, I began to see how similar we both are. We both have these imperfections and it's as if the world labels us by saying "you are this... or you are that." The beauty of it however, is that we can turn around and say "Yeah, baby! We are ghetto-fabulous!" And take that negativity and turn it into something positive. Prior to that, I was an actress. I'm like a walking left brain chick. My creative juices are constantly running—I play the Arabic drum, dance, do accents and absolutely love to travel. Growing up, my mother not only brought out our individual talents, but also brought it out of others as well, so that we could all enjoy this beautiful thing called life, together. So, no matter if we were in our restaurant with Indian dancers, or traveling abroad to other countries, we submerged ourselves and indulged in the beauty of each culture. My mother presented us with a rich, lavish tapestry full of exotic definition, color and texture, so, her bringing the entire world to us, one culture at a time, definitely shaped who I am today.

Who do you think your book speaks to and why?

DK: Because the ideas in this book are so universal, it really speaks to so many people. Primarily it is written for the Arab-American chick—the girl who steps into an upside down world full of contrasts the moment she steps outside—but it also speaks to every ethnic minority caught in the middle of the East and West, including Arab men. It speaks to bi-racial people, like Obama, who struggled with their identity. It even speaks to the Amish because, believe me, that little Amish girl, clip-clopping 5 miles an hour in her little horse and buggy in the middle of a bitter cold snowstorm, is painfully questioning how modernity and progression got such a bad rap. Deep inside she secretly wishes that she could get into that warm Mercedes Benz that just drove by. Trust me, she's in this battle, too. Even Americans will even identify with this book. Just look at our political landscape, we're in a deep cultural divide—we are torn between conservatism and liberalism. So, I think this book essentially speaks to everyone, because we are all struggling in one form or another to find our place in life.

Do you think thongs represent sexual "freedom" or consumerism and conspicuous consumption run amok?

DK: I really don't like thongs, but I would say they symbolically represent the "idea" of sexual freedom to a lot of people. I believe sexual freedom or empowerment is something that comes from within—its inside yourself. I think things are so out of control these days and people are really confused—now more than ever—about their own cultural and personal expectations. Western society tells them that unless they behave a certain way, they are not sexually empowered. In America, we have "Sex in the City" as an example of who we should be. Coming from a traditional background, an Arab chick might be tempted to overcompensate and go against her instincts, because she wants acceptance—but she doesn't have to. An Arab chick doesn't have to feel ashamed that she is conservative, and doesn't have to sleep with men to prove anything. But by the same token, if she chooses to enjoy her sexual freedom in that way, she should not be judged either. Only we can decide what is best for ourselves. Personally, I have a profound respect for sex. It is extremely powerful, especially for Arabic women. Because we understand it differently, we get even more attached and emotional about it. What's more, is that physiologically, men and women experience sex differently. Generally speaking, a woman feels that a man enters a very precious part of her being—her soul. So for her, it's more than just a physical experience—it is a spiritual bond. So, unless two people are on the same page, emotionally, I think it can become very confusing.

What is the spirit and intent behind the book?

DK: The spirit and intent behind the book is really about being true to yourself—hearing your own voice underneath the jarring noise blasting from both cultures. It's about taking the good from each culture and throwing away the bad—ultimately defining yourself, rather than being externally defined. The message is to live authentically without concealing any part of your ethnicity. I always say, "Don't be fake. Don't be someone you fundamentally are not—it's a real turn off." I think this book encourages us to take a hard look at ourselves, examine our issues, think, explore, change (if we chose) but ultimately accept, and be proud of who we are. It encourages us to become the best we can be. When we do that—when we cherish and appreciate the great things about both our cultures—we can then truly appreciate the beauty in our neighbor's culture. And we can celebrate life, passionately.

What do you think the fear is behind assimilation into a more western way of living?

DK: There are so many reasons we are afraid, and I hate to say it, but it all boils down to faith and control. Only when we understand our fears, can we overcome them. We as Arabic people have such a rare and beautiful culture, and I believe that some people are terrified of assimilating because once they do, they feel that they will lose those precious gifts which make us so unique. They are afraid they will lose their identities and purposes and become lost. And in all fairness, their fear is not unreasonable. For example, in the West, there is great freedom, but with that freedom comes opportunities, choices and temptations. What happens is that over time, people begin to replace the family's common interests with their own individual desires. And without the right balance, problems can result. In American society there is a 50% divorce rate, teenage pregnancies AIDS, mass shootings, isolation, and a basic break down of the family, community and values, so it's not unreasonable that assimilation into Western culture is viewed as undesirable. The problem comes in when we only see half of the picture and get stuck in that mind frame. There are wonderful aspects about American culture that the Arab culture lacks. One of the biggest things that infuriates me is when an Arab person comes to this country, make his millions, send his kids to school, and takes advantage of every single opportunity that this country has to offer – and then curses America! I cannot stand that. It's so ungrateful and disgusting. It kills me. America has wonderful things to offer, despite the bad. I love my Arabic culture, but I also love my American culture. Here you can speak your mind. Here you can take a 3 mile run in a public park with your sports bra on, midriff exposed, without anyone judging you. Here you can do as you like, without anyone having the right to tell you that you are wrong. Here is freedom—along with the freedom to choose. You can live like an Arab in America, but it is very difficult to live like an American overseas. Yes, it's true, in America, we have a 50% divorce rate, but what that also means is that I don't have to stay married to someone I am completely miserable with. And I don't have to feel ashamed or judged for decisions regarding my own happiness. Here we can speak our mind. Here we have opportunity. Here we have the freedom to choose what we see best for ourselves. So, it's critical to look at the whole picture—and then decide. No culture is perfect, so you have to look at the good and bad with each. The truth is that we are all guilty on some level, but the bottom line is that trust—not fear—should be the basis of assimilation. Trusting ourselves frees us up to being open to new ideas, while simultaneously remaining confident enough that we will hold on to the good "old" ones, and not get "lost". And that, my friend, is the real secret to balancing the East and the West. To learn more about the book and buy it, click here.

Dana Point, Ca 92629

USA +1 (949) 743-2535